And yet another scandal. «They Don’t Care About Us» even managed to break the controversy record previously set by «Black or White» — because this time there were two scandals at the same time. First, the US Jewish community was disturbed by the lyrics because it allegedly contained anti-Semitic words (the lyrics to this song is being discussed to this day). Then the Brazilian government did exactly what the good old Communist governors in the USSR used to do – «we maintain that everything is fine in our state, and whoever doesn’t think so will be silenced.» And even Pele, a nice man, a great football player and a national hero, supported this point of view. Perhaps, the most irritating thing for everybody was that Michael Jackson, who had been indifferent to politics up to that point, suddenly released a song that manifested his views very directly: “You know I really do hate to say it, the government don’t wanna see…»

June, 1995: Soon after the release of the HIStory album, a scandal flares up about words “jew me” and “kike me” used in «They Don’t Care About Us.» Michael is forced to apologize for using these words. According to CNN, the controversial fragments of the lyrics will be rewritten to sound like “do me” and “strike me.” Later these words are masked by sound effects, and History is reissued with a new version of «They Don’t Care About Us.» The original version of the album is a collector’s item today.

June, 1995: Soon after the release of the HIStory album, a scandal flares up about words “jew me” and “kike me” used in «They Don’t Care About Us.» Michael is forced to apologize for using these words. According to CNN, the controversial fragments of the lyrics will be rewritten to sound like “do me” and “strike me.” Later these words are masked by sound effects, and History is reissued with a new version of «They Don’t Care About Us.» The original version of the album is a collector’s item today.

February, 1996: Scenes for one of the two «They Don’t Care About Us» short films (known as “the prison version”) have already been filmed in a real prison in Queens, New York. Michael Jackson is planning to go to Brazil to shoot the second version of the short film. Meanwhile, the Brazilian authorities intend to prohibit the filming – some of the government members expressed their dislike towards the project as, in their opinion, it would show Brazil in an unfavorable light; yet others approved of the idea hoping that a Michael Jackson video would draw the world’s attention to the Brazilian poverty, and the region might even get some help. Brazilian officials are mostly concerned that the video will show impoverished districts of the city – Brazil is hoping to win the right to host the Olympic Games, and a demonstration of the Rio slums may affect their chances of hosting the Olympics in 2004. Residents of Rio de Janeiro favela are, nevertheless, very happy that the world will finally get to see their living conditions.

February 6: A day after the Brazilian judge gave permission to film the video for 20 days, he suddenly changes his mind and reduces the filming period to 5 days only.

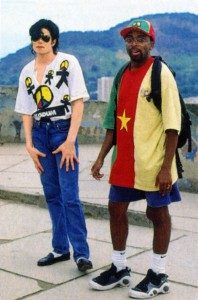

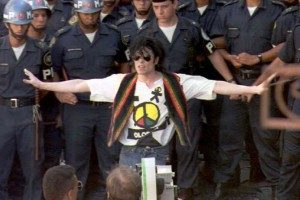

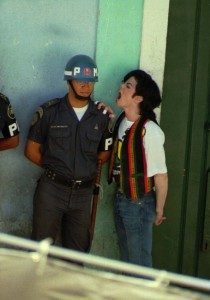

February 11: Michael arrives in Rio. A day earlier, Spike Lee already started shooting in the central district of Bahia. The favela is shot in Rio; Michael’s dance with the Olodum band (a worldwide known Brazilian drum band consisting of approximately 200 members) and the scene where a young woman breaks through the cordon to hug Michael are shot in the historical part of another Brazilian city, Salvador. The territory where the filming takes place is protected by 1500 policemen. Michael dances for six hours straight (just two months after he collapsed during a rehearsal in New York on December 6, 1995). In the beginning of the video, a girl speaks in Portuguese, “Eles nao ligam pra gente,” which means “they don’t care about us.”

March 23: Global (except for the USA) premiere of the Brazilian version of “They Don’t Care About Us” short film. On MTV Europe, the video is broadcasted at 1 pm in program «First Look.»

April 16: “They Don’t Care About Us” debuts at No. 5 in the European chart. It also debuts at No. 9 in Sweden and at No. 4 in England (the fourth single off the History album to make a debut in the Top 5 in Great Britain).

April 22: “They Don’t Care About Us” short film is banned from broadcasting on MTV USA and VH-1. It was shown by MTV USA only once, with a notice of withdrawal from further rotation. The decision is caused not by the footage, but by the lyrics of the song.

June, 1996: “They Don’t Care About Us” short film is staying at No. 1 in the Top 20 on European MTV for several weeks. French musical channel MCM plays both versions of the short film without restrictions. (MCM also plays «Scream» short film without sound or video cuts, unlike MTV.) The prison version is prohibited on several music channels due to scenes of violence contained in the short film.

The fall of 1996: One of Brazilian football teams uses “They Don’t Care About Us” as its anthem and performs a ritual dance, copying Michael’s movements from the video, before each game to scare and demoralize the opponents.

September, 1997: MTV Europe starts showing the prison version of “They Don’t Care About Us” short film, but only after midnight.

The Director

Both versions of «They Don’t Care About Us» short film were directed by the same director, Spike Lee. The atmosphere of both videos clearly bears the influence of the two extraordinary people and great talents — Jackson and Lee; you can feel the pivot of energy created by this powerful duet. Spike Lee is a famous movie director. His movies “Jungle Fever,” “Get on the Bus” (Michael lent song «On The Line» for this one) depict problems of racial and social relationships – for instance, they tells what happens when a black man falls in love with a white woman and how their milieu reacts to this. These are powerful and sincere movies, and Spike Lee is an outstanding director whose achievements in films have been acknowledged and appreciated. So it is really interesting to hear his impressions from working with Michael Jackson.

Both versions of «They Don’t Care About Us» short film were directed by the same director, Spike Lee. The atmosphere of both videos clearly bears the influence of the two extraordinary people and great talents — Jackson and Lee; you can feel the pivot of energy created by this powerful duet. Spike Lee is a famous movie director. His movies “Jungle Fever,” “Get on the Bus” (Michael lent song «On The Line» for this one) depict problems of racial and social relationships – for instance, they tells what happens when a black man falls in love with a white woman and how their milieu reacts to this. These are powerful and sincere movies, and Spike Lee is an outstanding director whose achievements in films have been acknowledged and appreciated. So it is really interesting to hear his impressions from working with Michael Jackson.

“I’ve met Michael a couple of times. He got an award in New York City a couple of years ago from the United Negro College Fund as the Performer of the Year. Michael came to my house in Brooklyn, we sat and talked for four hours about the arts, movies we like, musicians — just the stuff we admired… And I mentioned to Michael that, on his History CD, there was a song I would really love to do a music video for, this great ballad Stranger in Moscow. And Michael said, ‘You do music videos?’ ‘Yeah, Michael, I do lots of music videos.’ So I gave him the reel with the stuff I’d done, and he said, ‘Great!’ Then the next time he called me back he said, ‘I want you to do Stranger in Moscow, but let’s do They Don’t Care About Us first.’”

“The original concept was not meant to be two videos, the prison stuff was going to be combined with the stuff we shot in Brazil. The marching orders Michael gave to me were that he wanted it to be hard-driven, he wanted the spark, an edge to it. He wanted to see a lot of archival footage in it that would chronicle man’s inhumanity to his fellow bothers and sisters. And using that as a starting point, we came up with this idea of Michael being one of many convicts in this prison.”

“Everything he’s involved in, he wants it to be the very best it ever was. That’s a great attitude, and it’s also a great responsibility. And in everything he does, he told me, ‘Spike, I want this to be the best’ – he doesn’t call it a music video – ‘I want this to be the best short film ever!’ I said, ‘Okay, Mike!’” (laughing)

(On the video set) “Mike said he was gonna try to drive the crowd into a frenzy, and he did. And these two ladies jumped out from the crowd — security was lacking on one side, so these ladies jumped out, grabbed him, he fell to the ground! (laughing) I picked him up… and I asked the cameraman later, ‘Did you shoot it?’ and he said, ‘Yeah, and I’ve got you too.’ That was very funny. We did not plan this, that was not rehearsed, they just broke through, and it was exciting….

…Michael has a plane waiting, he has to be in New York with his crew tomorrow, so we’re gonna try to get as many shots as we can before Mike has to jet.”

“Here in this Brazilian video, you can see the love Brazilian people have for Michael. It’s out there. Shooting ‘They Don’t Care About Us’ with Michael Jackson in Brazil was one of the highlights of my career, and I’m including the feature films. I just had a great, great, great time. I think it was historical what we did. It was awesome.”

Opinions

Spike Lee (about problems with getting a permission to film in Brazil): “Michael loves Brazil and the Brazilians and he doesn’t need to go half way around the world to show that shanty towns exist in Rio. This is ridiculous and pathetic. We’re not trying to topple the Brazilian government. In the eyes of the world, complicating Michael Jackson’s visa is making Brazil appear a ridiculous country — as if it were a banana republic.”

Spike Lee (about problems with getting a permission to film in Brazil): “Michael loves Brazil and the Brazilians and he doesn’t need to go half way around the world to show that shanty towns exist in Rio. This is ridiculous and pathetic. We’re not trying to topple the Brazilian government. In the eyes of the world, complicating Michael Jackson’s visa is making Brazil appear a ridiculous country — as if it were a banana republic.”

Bob Jones (about video ban due to the lyrics): “Michael is not a racist, as evidenced by his many endeavours on behalf of people of all religions.”

Michael Jackson (on accusations of anti-Semitism): “It’s not anti-Semitic. Because, I’m not a racist person. I could never be a racist. I love all races of people — from Arabs, to Jewish people, like I said before, to blacks. But when I say, “Jew me, sue me, everybody do me, kick me, kike me, don’t you black or white me,” I’m talking about myself as the victim, you know. My accountants and lawyers are Jewish. My best friends are Jewish — David Geffen, Jeffrey Katzenberg, Stephen Spielberg, Mike Milkin. These are friends of mine. They’re all Jewish. So how does that make sense? I was raised in a Jewish community.”

Considerations

Never before has Michael Jackson spoken about the political aspect of social problems; sometimes he was asked in an interview what he thought of politics, but he always responded sincerely that it was all Greek to him.

Never before has Michael Jackson spoken about the political aspect of social problems; sometimes he was asked in an interview what he thought of politics, but he always responded sincerely that it was all Greek to him.

Since Michael became a superstar, the USA has changed three presidents, and Michael met each of them – Reagan, who was the first to invite him to the White House, Bush-senior and Bill Clinton at whose inauguration Michael performed and whom he apparently liked the most. But all this had nothing to do with politics – just with Michael’s inexhaustible curiosity and desire to see everything with his own eyes. And is there a politician who doesn’t seem charming during a half-an-hour conversation at the official reception? Michael probably had neither time, nor desire to try to understand their character or work any deeper.

The Americans don’t need to understand it deeply anyway, as they don’t depend on the personality of the current resident of the White House as much as we do. So an average man may allow himself not to think about these things. And for a very long time, Michael seemed to worry only about those problems that depended upon our common consciousness and awareness, such as people’s attitude towards nature and their surroundings (many of Michael’s songs are about this – “Heal The World”, “Man In The Mirror”, “Jam”, “Keep The Faith”). These are our problems, the solution to them is in our hands, and no government can help us solve them or prevent us from doing it. But there were other problems too…

Those “other” problems stormed into Michael’s life unceremoniously and suddenly. After finding himself a victim of a fabricated accusation, he must have come to a realization that the seemingly inviolable laws did not always work. Presumption of innocence, a sacred principle, turned out to be an empty word. An average man thinks that money and fame solve any problem, but Michael found out they didn’t help him either.

Trying to get out of this nightmare, Michael probably kept wondering how a common humble man would feel facing the government and judicial system – a humble man who couldn’t afford to hire the best lawyer, for whom no celebrities would speak, and who didn’t have thousands of loyal fans. And even if it’s true that everybody’s equal before the law, a humble man is clearly powerless and vulnerable. And having experienced this notion of “equality of rights,” or, to put it better, “equality of no rights,” Michael spoke his mind in a song on behalf of a humble man.

The song is a first-person narration, and in its refrain, the superstar relates to problems of common people. “They don’t really care about us” means “you and me.” Someone else could have written “they don’t really care about people,” but not Michael. For him, this notion of us is absolutely natural, almost sacred. Rumor has it that Michael Jackson is isolated from the society — sometimes this observation even used to justify his behavior. This may partly be true, but not when we talk about the empathy and ability to relate. Michael Jackson considers himself a common citizen and is not afraid to speak like one. And isn’t it true? Doesn’t the major part of Michael’s problems lie in the narrow-minded prejudice and everyday racism of the society?

If we analyze the very essence of the negative attitude towards Michael Jackson expressed by many people, we will sure find double-dyed extreme uncouth racism in all its ugliness. “Don’t you black or white me” is a deeply personal line, but it’s not a problem of people’s attitude towards Michael specifically, it’s a global problem. And that’s just one line in that song.

Michael didn’t know what to do with this – being a law-abiding citizen who never conflicted with authorities, he had nothing to offer; for him, it was just one of those conditions that “makes you wanna scream.” Here I will quote Olga Petrova from Krasnoyarsk who made a very astute observation:

Michael didn’t know what to do with this – being a law-abiding citizen who never conflicted with authorities, he had nothing to offer; for him, it was just one of those conditions that “makes you wanna scream.” Here I will quote Olga Petrova from Krasnoyarsk who made a very astute observation:

“At first, I thought that there was something unfinished about the TDCAU short film, something missing. Now I realize that it is the very thing that was never intended to be there – the energy of aggression, destruction, a call to arms. (This may sound unpleasant, but in our everyday lives and in our souls, we more often see manifestations of the aggressive energy fuelling accusations, and not the energy of resistance empowering self-control and fortitude against repressions.) There is no spite and no spirit of revenge in this song – no accusation, only a protest and an indignation. You could say that this song is about civil disobedience.»

The content and energy of the song stay within boundaries so prudent that it’s nearly impossible to find any aggressive notes in it. “All I wanna say is that they don’t really care about us” – one can hardly address this matter with a more reserved and delicate line.

In a way, during that period, the Michael had a personal need for public statements, such as “beat me, hate me, you can never break me,” as much as he saw a social need for them. The song sounded then and still sounds today like a manifest of spiritual endurance and disobedience against the deliberately lying accusers. If we approach the song in this way, seeing it as both personal and social, it’s easy to see why Michael released two different short films for the song – the prison version with a powerful documentary drama and the flamboyant Brazilian version.

In the Brazilian version of the short film, policemen who look stern and indifferent to the festive whirlwind of colors and rhythms are probably the only thing that reminds us of the social meaning of the song (otherwise you might think city dwellers celebrate something) — the lively joy and free self-expression of people is under vigilant control, and you can never be sure that this freedom won’t be suppressed.

But the prison version is completely dedicated to the social theme. The short film uses imagery that is harsh to the point of being uncomfortable to watch. (Michael used documentary footage of the student rebellion on the Tiananmen Square in China, of brutal police beatings of African Americans in Los Angeles, as well as footage from the Vietnam war.)

But the prison version is completely dedicated to the social theme. The short film uses imagery that is harsh to the point of being uncomfortable to watch. (Michael used documentary footage of the student rebellion on the Tiananmen Square in China, of brutal police beatings of African Americans in Los Angeles, as well as footage from the Vietnam war.)

The ghosts of the beaten people are haunting Michael even in his solitary cell: these are not just television images, there are real life pictures – a horrible reality of human humiliation and suffering that surrounds us everywhere, breaking into our everyday life, our minds, depriving us of peace, leaving us no place to hide. The short film revives the images of Roosevelt and Martin Luther King who, according to Michael, “would not let this be.” (It could be argued that this line is supposed to expresses the opinion of an average man – a white man for whom Roosevelt is the most honorable and honest president, and a black man for whom Martin Luther King is the embodiment of the very spirit of the American civil rights movement.)

The tension in the video is palpable, and yet we observe an amazing scene: it is not a revolt, a mutiny or an escape, but a totally peaceful riot not suppressed by the prison guards. It looks like Michael «lightens» the message of his leadership on purpose. He expresses his angry protest too explicitly, with demonstrative insolence — sweeping tableware off the tables and hitting a guard’s baton right in front of his face. Notice that Michael is the only prisoner who moves freely around the prison’s dining room, creating an impression of a somewhat light-headed mischief, irresponsible for the consequences of this daring game. It is simply a demonstration of protest against the disregard for human rights and laws by the authorities.

Michael is trying to convince people to fight for their rights, raising the spirit of protest against oppression and humiliation — but, of course, prison riots never end at slamming fists against the table or dancing on top of it, and Michael knows this very well. The real life problem is that a call to fight “for freedom and independence” can easily erase the line between the good and the evil, between a disobedience and an attack… And the spirit of protest easily mutates into the spirit of revenge, inflicting violence on those who oppressed our dignity and freedom.

The last scene of the video shows — in Michael’s own unique way — his confusion about what he should do with his leadership in these circumstances. While his scream is still lingering in the air, Michael, already free, is running up the stairs, glancing back — running away from the prison, the riots, his own scream and himself… Leaving an unspoken question, “I don’t know what lies ahead… Where will this spirit of struggle lead me, where will it further manifest?”

One more conclusion deserves to be highlighted: Olga noted very astutely “how naturally and confidently Michael expresses the pain and anger as a messenger of the Nature (in ‘Earth Song’), and how unsure he is of his role when speaking about the pain and anger of humans (in ‘They Don’t Care About Us’).” It’s harder to stand up for people – primarily because people (unlike the Nature) are oftentimes the ones to blame for their own troubles and misfortunes.

The question of whether the use of the «controversial lyrics» in «They Don’t Care About Us» was appropriate is still open. Right now Jennifer Lopez has to deal with her own share of trouble because of using the word “nigger” in one of her songs; I guess these matters are not as simple they seem to us. To us, this may look like a silly superstition, but I talked about this to a girl from the USA once, and she told me that “the context for bad words doesn’t matter – the very fact that a superstar is using them can set a bad example.” It sounds quite strange, considering the range of obscene words per minute of an average Hollywood blockbuster… But perhaps, this is a matter of mentality that has to simply be accepted.

As for the Brazilian controversy, the story is ridiculously plain. Michael sang that the government didn’t care about people, and the Brazilian government illustrated this perfectly. The Brazilian authorities worried about their money and reputation of the country — clearly not understanding that they only undermined it more by trying to create obstacles for Michael Jackson, — but they didn’t care about the population of the Rio slums. (Authorities in developing countries often have this difficulty — the lack of flexibility of thinking.) But those half-naked tanned boys and girls, children and adults (and we, too) understood once again that there was one person in the world who would always care for us.

Article by Anastasia Kisilenko, 2001.

The article was published in Dangerous Zone fanzine, Issue 13-14.

"If Martin Luther was livin'/ He wouldn’t let this be/ Skin head, dead head / Everybody’s gone bad" sang Michael Jackson in the song "They Don't Care About Us."

Taken from the album HIStory: Past, Present and Future – Book I, released in 1995, "They Don't Care About Us" is probably Michael Jackson's most politically-engaged track.

And with good reason. The song openly discusses racial discrimination, skinheads, Martin Luther King, and the passive stance authorities often take against injustice. "All I want to say is that/ They don't really care about us," crooned the King of Pop, implicitly referring to people of color in America.

Aside from the political lyrics which are still extremely relevant, one version of the video clip has been getting a lot of attention now, over twenty years since its release.

Both versions of the video were directed by Spike Lee, who is known for his activism on behalf of people of color, as is evident in his filmography which includes Jungle Fever (1991) and Malcolm X (1992).

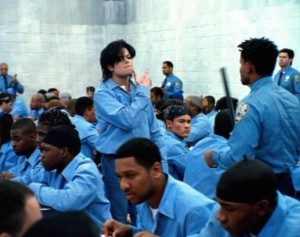

Michael's version was a big hit at the time. In the clip, he appears handcuffed in a jail cell before going on to dance in the middle of the prison cafeteria filled with mostly black prisoners.

The inmates begin to protest, while archival images flash onscreen portraying historic police violence, famine in Africa, human rights violations and Ku Klux Klan gatherings.

Modern relevanceIn a divided America that often prefers to ignore racial tensions, the video for "They Don't Care About Us" feels pretty provocative.

Particularly since it came from one of the most iconic black pop musicians of all time – who also happened to be adored by the white middle class. Due to the controversial content, the clip was actually censored in the 1990s, and MTV and VH1 would only air it after 9pm.

In the days following the death of 32-year-old activist Heather Heyer in Charlottesville, references to Michael Jackson's video have been popping up all over Twitter. Many shared the clip online saying the images and content took on even deeper meaning in Trump's America.

The first version of Michael Jackson's 'They Don't Care About Us' video which was refused to be played on tv & we know why. ☻ pic.twitter.com/FCw0pNqlyh

— Hanan. (@USoulSurvivor) August 13, 2017

A tweet asserting that "the first version of Michael Jackson's 'They Don't Care About Us' video... was refused to be played on tv & we know why" has been liked by over 160,000 people and retweeted over 106,000 times.

And if we needed any further proof that the clip still has a strong impact, the comments section under the video on YouTube recently had to be deactivated because the debates were getting too violent.

"They Don't Care About Us" seems like the perfect anti-racist anthem for these trying times.

Source: https://www.konbini.com/en/politics/michael-jacksons-they-dont-care-about-us-gains-new-relevance-after-charlottesville