Uri Geller about MJ - My Friend Michael Jackson (2001)

"This, I promise, is how you will react when you meet Michael Jackson: you’ll stare, you’ll start, you’ll step up and you’ll freeze. Everyone does the same thing - fans, celebrities, journalists, children, parents, shoppers, waitresses, prime ministers, prime ministers’ bodyguards ...

First you look. Michael has the most arresting appearance of any man I ever saw. It isn’t only the face, and the clothes. It’s the aura. But before you have taken that in, you’ll start to move towards him. Instinctively.

You take a step or two, and freeze. It’s like being hit by a wave of awareness, first of all pushing you forwards and then stopping you cold in the backwash. “Oh my God it’s Michael Jackson” and then “Oh! My God. It’s Michael Jackson ...”

I’ve been in the massive lobby of an international five-star hotel when Michael walked in, and I’ve seen the wave sweep over 70 people - not only the super-rich and the professionally cool, but the porters and receptionists and bell-boys.The people nearest him moved, and then froze. Further away, people turned, and moved, and froze, while some of those nearest began to move again. It was like a century-old fragment of celluloid, the lobby suddenly silent and the air flickering, crackling, as people moved in jerks and lurches. Michael simply smiled and pressed his hands together in greeting.

Last month we drove out of his Knightsbridge hotel in a people-mover with midnight-tinted windows, and there were 2,000 people crowded across the pavement. Around 60 of the younger ones broke from the press and sprinted alongside us. I was concerned that someone could slip and fall under a wheel, but they were all so exuberantly happy. They were shouting out, “Michael, we love you!”

Michael gestured for the car to slow down, and he edged his door open, leaning out of the car to touch the hands of his fans.

“We love you, Michael!”

“I love you more,” he said. I heard him say it again and again during the next few days. “I love you more.”

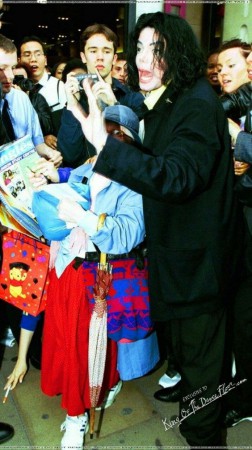

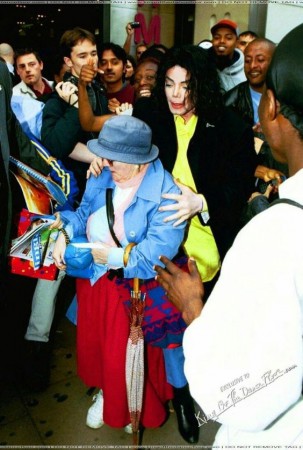

When Michael walks over to a group of fans who have waited hours for a glimpse, you see some of them lock solid. They have messages for him, they want to say how much he has meant to them all through their lives, how his music has been their soundtrack, but all they can do is stare.

Many bring handmade gifts. Embroidered cushions, framed paintings, poems, boxes, candles, national flags. He takes every one and holds it to his chest for a moment. He says, “Thank you. I love you,” again and again. He does not refuse any request for an autograph or a photograph. I walked with him for 200 yards through the pouring rain across an Oxford road and past barriers after his address to the privileged Union audience last month, to a huddle of drenched and shivering fans. They had not been able to get tickets, and they had turned up on a bitter night without any real hope of being close to Michael for more than a moment, but they (and not the curiosity-hunters in the Union building) were the real fans.

Michael truly loves his fans. When he tells them, he does not do it in the superficial way that most pop stars intend when they shout it from the stage. He means it this way - when Michael walked through the rain that night, he was on crutches, with two broken bones in a foot that was swaddled in bandages. By the time we got back to the limousine he was squeezing filthy, icy rainwater out of the bandages onto newspapers on the floor. I laid my hands on the aching flesh and let energy flow through me, to activate Michael’s own healing powers. He sat back with a calm expression on his face and his eyes closed, perfectly accepting of the possibility that healing can begin with positive thinking.

The fan’s gifts are displayed in Michael’s hotel suites. Wherever he’s staying - and he moves around a lot, even between places in the same city - his favourite presents are on display. And he has a lot of favourites. He uses objects almost as pledges, reminders of affection from people who can’t be with him, the way you might fill your wallet with photos of your children and folded postcards from old friends. On Michael’s walls there are pictures of his own children, of course, and photos of him with his family and friends, but the reverence with which the admirers’ gifts are arranged seems to say that his fans are his family too.

I saw how sincerely he felt this when two ingenious German über-fans broke into my home on my wedding day. Michael was to be best man, though by the time the ceremony was due to start neither he nor the rabbi, Shmuley Boteach, had turned up. My manager, Shipi, who is also my brother-in-law, had posted security guards all round the perimeter of the grounds. We were tolerating half a dozen paparazzi who were pointing lenses like cannon barrels over the privet hedge which screens the house from the Thames, and there were a few girls perched in the riverbank trees too, with nothing to see but the marquee and a helicopter. Once or twice the magician David Blaine floated outside for interviews - I do mean floated, and if you haven’t yet seen David Blaine levitate then you have a real shock in store.

Many guests commented that I seemed nervous, and I was -but not about getting married. Hanna and I had been together 30 years, and I felt I was probably ready for the commitment. What concerned me was a call from an Israeli source, warning there might be a terrorist attack on the wedding. I took the warning very seriously and I engaged all precautions, Scotland Yard referred me to the local police who in turn sent two policemen to discuss the day. Some internationally famous people were there, aside from Michael - the Formula One racing champion Nigel Mansell, Sir David Frost, Dave Stewart of the Eurythmics, the horror writer James Herbert, Dido’s producer Youth, not to mention an Israeli consul and the Japanese Ambassador... any terrorist wanting to make a name for himself need only open fire on the canvas walls of the marquee with an automatic weapon. My helicopter pilot was under orders to fly anyone wounded by gunfire to the nearby Royal Berkshire hospital. A medical doctor was on standby, unseen by the guests inside the main house, and Michael’s own doctor would accompany him.

Most of the fans, with no thoughts of terrorists, were outside the main gates. A steady stream of guests drove up and announced their names to the guards. The Germans, a boy and a girl, were clever and brazen - they hung around to hear a couple announce themselves, walked away for 20 minutes, then came back and presented themselves under the same names. Shipi saw them walking down our long driveway: “Who’s that?” he demanded nervously, but by then the Germans were inside, and we didn’t want a scene. Not in front of the paparazzi. Not on my wedding day. If these guys were willing to behave themselves ... and they were, but they pleaded to be allowed close enough to say hi to Michael when the ceremony had been concluded.

Most of the fans, with no thoughts of terrorists, were outside the main gates. A steady stream of guests drove up and announced their names to the guards. The Germans, a boy and a girl, were clever and brazen - they hung around to hear a couple announce themselves, walked away for 20 minutes, then came back and presented themselves under the same names. Shipi saw them walking down our long driveway: “Who’s that?” he demanded nervously, but by then the Germans were inside, and we didn’t want a scene. Not in front of the paparazzi. Not on my wedding day. If these guys were willing to behave themselves ... and they were, but they pleaded to be allowed close enough to say hi to Michael when the ceremony had been concluded.

Michael did more than say hi. He beckoned them to him, embraced each of them gently, accepted their gifts graciously and posed for their cameras. He told them he truly valued their friendship, thanked them for taking such risks to bring him presents, and smiled a blessing upon each of them.

Now, you may be cynical about Michael Jackson. You may be influenced by the highly inventive controversies which have dogged his career. You may be prejudiced by his appearance - though you’d better ask yourself why you feel free to comment on his colour and his looks when you profess that you never judge anyone by their skin or their face. You may feel that I’m painting him as some kind of saint, when some supermarket tabloids are eager for you to believe the opposite.

I won’t bother to argue with you. Michael has maintained the dignity throughout his career to ignore the mudslingers. I know what it is to be falsely accused and reviled, to be laughed at by people who don’t have the first idea of what they’re saying - but I thank God that the mud aimed at me over the decades has been nothing like the rancid filth hurled at Michael. I have nothing but contempt for some of the people who made such claims, nothing but pity for the people credulous enough to believe them.

All I will say is this: how many other people, now or at any time in history, have possessed the charismatic power to change lives with a smile? To offer a blessing and make a person feel deeply, fully blessed? And how many of those people kept their gift uncorrupted and used it with generosity? There are a few names in your mind perhaps, but I won’t make the comparison with Michael. I will leave you to do that for yourself. Let it be a test of how open-minded you can be.

Most people who achieve great fame taste this power, this unexpected gift from God to bestow inspiration on people. Michael has it to an exceptional degree, and this is partly because it has been his to wield for so long. Most sports stars and rock gods lose it after a year or two, as their fame fades. Or they push it away from them without understanding it. Or they foolishly imagine it will protect them from the ravages of their drinking and drug habits. Michael treats the gift with awe, as if it were a healing power ... which it is. A smile from Michael can heal the spirit. He has an angelic talent for choosing words which will touch the heart. I treasure the inscription on a photograph he gave to me, because he wrote without holding back: "To Uri, you are truly a Godsend. The world needs you - I need you. Michael”

When I perform, particularly when I have to bend spoons again and again, I feel drained afterwards. It’s not the tiredness that comes from hard labour or long study or too much partying - it’s an ennervation, as if I’ve been sweating raw energy and all my nerve endings are swollen and raw. I often sleep in the back of the car. When he is exhausted, Michael meditates. After the wedding was over and the celebrity photos were all done, he asked me for a room in my home where he could be alone for 20 minutes. Michael is not a frail man, despite what you may have read - he is tall, lithe and his hands are large and strong, like a tennis player’s. But at this moment he looked like the finalist after five sets on Wimbledon’s centre court. He needed peace of mind.

I showed him into our family room, with its tables of crystal globes and pyramids and its lifesize wooden effigy of Elvis in his rhinestone phase, and left him to meditate. Maybe the spirit of Elvis came to him - the Pop Prince was once the King’s son-in-law, after all. When he emerged, he seemed still tired, but more centred.

Michael’s family was famously religious - they were Jehovah’s Witnesses and Michael occasionally disguised himself to join his fellow believers as they went from house to house, inviting people to think about God. As a grown man, he has moved beyond denominations of faith - his concern is not with religion but with spirituality. This gives him strength, but I think it is the joy he takes in life which keeps renewing his vitality - that, and a second factor which I shall describe in a moment.

He has a lot of fun, childish fun. Not just child-like, but downright fun. He giggles a lot. He has a great sense of mischief. Michael first became aware of me through reading his school textbooks when he was a teenager. We were introduced by Mohamed Al Fayed, a man whose grasp of English is often variable but whose fluency in swearing is unmatched in any language. Even Hungarians don’t swear as enthusiastically as Mo. I think he is spurred on by the presence of people who might be easily offended, like little old ladies or royalty. Or pop royalty - when Mo starts cursing in front of Michael, the tirade is punctuated by delighted giggles and, “Oh, Mohamed! Ohhhh, Mohamed!”

He loves gadgets. Show him a watch that’s calibrated via a satellite link to the atomic clock, or a digital writing pad with a built-in camera, or a mobile phone with a scanner, and he’s like a boy - “That’s cool, I love it, can I have it? I mean, just play with it?” He surrounds himself with boyish paraphernalia -pictures of dolphins and sunsets, huge teddies and model cars. He’s not into sport much, though he’s very fit, like any professional dancer, and he supports newly-promoted Fulham - in the casual way that a lot of teenagers say they support Manchester United, not really understanding the rules or remembering the results, but happy to relate to the team that always wins. Plus, of course, Fulham are owned by a friend of his - Mo took him to a game and they sat there in Fulham scarves and caps. Michael has infinite respect towards Princess Diana who tragically died with Mo’s son Dodi whom Michael adored; they were working on a movie together.

Michael’s hotel rooms are always decorated with movie posters and eight-foot cardboard cut-outs, Anakin Skywalker peeping out from the folds of Darth Maul’s cape, E.T. bicycling over the full moon. The first time I visited him in New York we hired Sony’s cinema and took in The Matrix, because there’s a sequence inspired by me where children teach Keanu Reeves to bend spoons with the power of the mind.

Michael brought popcorn and candy, and his little boy Prince rocketed around between the seats, stopping every few moments to fix me with his luminously intelligent eyes and ask a question. After about half the movie, Michael slipped out of his seat. I didn’t say anything and I thought that maybe this was his way of avoiding a ‘goodbye’ moment. But after four or five minutes I twisted round and saw him, silhouetted under the projectionist’s beam. Dancing. Moonwalking to the soundtrack, spaced out in a complex routine of twists and jerks. Anyone could have seen that it was Michael Jackson. No one else on Earth moves that way.

He took me to his studio, the Hit Factory - it isn’t his own, he merely hires it, but when Michael walks into the recording area it becomes his. He dominates the studio, a different kind of domination to the way he overwhelms a crowd. This is business, and this is the second factor which restores his youth. Michael is utterly committed to his music. He works passionately at it, with a dedication that surprised me when I first saw it. I had deliberately ditched all my preconceptions about this man, because I’d known about his music and his life since I was a young paratrooper and later a paranormalist doing shows for Israeli troops, three decades ago. All that second-hand clutter wasn’t going to help me understand the real human being. But in our few meetings and a series of increasingly deep telephone conversations, I had not divined an artist who could be so forceful, so powerful, in the studio.

His attitude shines out of him like an aura. Writing, performing, mixing, arranging - he is in command. Always a confident person who will say what he means even though he says it quietly, in the studio his confidence reaches an entirely different level. He is dominant. And nothing pleases him more than honest praise from another musician. Michael’s face was radiant when I told him that Justin Hayward, guru of the Moody Blues, had called me from his home in France especially to tell me to pass a message to Michael: you have never made a record that was less than excellent, he said, and this is almost unique among artists of your longevity. I think he took pride because he knew it to be true. There is not one poor disc. Perhaps not even one poor track. Simply a catalogue of stone classics. I am proud of myself that Michael liked my own paintings enough to commission a piece of art for the sleeve of his forthcoming CD. And I was totally flattered when he asked me to energize the tapes which were in the studio’s safe.

It wasn't the first time I have worked in this way with super performers. I visited the Spice Girls in a studio in London around five years ago, they were planning to go to America and I bent a spoon for them and told them to take it with them to the US to bring them positive energy. It was a similar experience with N'Sync, they were playing small shows in Germany and here (the UK) and wanted to break in America I went to see them, talked to them motivated the group bent a spoon for them and said keep this with you as a talisman as a tool for your mind when you go back to America. Both bands have been catapulted to success.

John Lennon and I become close in the seventies, I lived a block away from him in New York and we would meet up about once a month in secret to talk about UFO's. When John wanted Yoko to come back to him he asked for my help. I had a meeting with Elvis too, he requested that we meet about 20 miles outside Las Vegas, he wanted the meeting to be private and told me where to meet him in the desert in a trailer - he was amazing.

Iintroduced Michael to my friend Rabbi Shmuley Boteach, who was writing a book of letters, The Psychic And The Rabbi, with me, and together we took Michael to the Carlebach Shul in New York for his first visit to a synagogue. We chose this setting because Rabbi Carlebach was famous for his music and his singing. Jewish worship is filled with song, and Michael’s face was a picture as he swayed and clapped with the music. I saw the same expression in his eyes when I glanced down at him under the chupa, the traditional Jewish wedding canopy, as our guests lifted Hanna and me onto their shoulders.

It was during the synagogue service that I began to understand how Michael’s gift for bestowing blessings might be most generously spread. Shmuley had the same idea and, as he was moving to New York from Oxford, England, with his wife and six children (it’s seven now), the rabbi was able to put his particular gift for practical energy to good use - together, they founded the charity Heal The Kids.

My concept was more abstract. Tormented by the disintegration of the peace process in the Holy Land, I wanted to hold up the almost supernatural aura which emanates from Michael when he is giving hope and happiness to his fans, and shine that like a beacon over Israel. I had no idea how this could possibly be done - I just could not fathom a world where soldiers shot at children who threw stones at cars, and snipers who took aim at babies, while millions of people of all races, creed and colour on other continents loved a man who reflected their affection back so dazzlingly. That contradiction just floors me. Everyone in Israel has heard of Michael - his concert a few years ago was a massive sell-out. Everyone would have recognised, at a single glance, his dancing image at the back of that cinema. So what’s to prevent his gift of peace from working in Israel?

I remembered a stone I had picked up in the Sinai desert, close to the monastery of St Katerina, when my father and I drove out there one day after the Six Day War. I was recovering from my wounds that I suffered in Ramallah and I believe my dad was proud of me at that time as he never was before or since - my father was a professional soldier. We tried to imagine the place where God had spoken to Moses from the centre of a blazing bush. When I sensed I had found the place -and I can still feel the electric tingle in my palms and fingers, the dowser’s sensation that decades later told me when I had discovered gold or oil - my father helped me dislodge a stone.

Moses’ foot may have trodden on this triangular piece of rock. We prised it out of the ground and brushed the sand off it, and carried it to the jeep. We drove back to Jerusalem, and close to the Western Wall I placed the stone on the ground. Whenever I returned to the city I went to look at it.

But after the Carlebach Shul, I went back to do more than look. Shipi persuaded a guard to look the other way while I prised the slab out of the earth for a second time and loaded it into a suitcase. I won’t tell you all the difficulties I had getting that suitcase through El Al’s security cordon and past US customs, but at one stage I seriously feared the stone would be smashed to shards. Finally, I put it beside me in a yellow cab and called Michael to tell him I was bringing a present. I called it the Stone of Peace.

More than a year later, as Shmuley and I posed for photographs with Michael and the Prime Minister of Israel, Ariel Sharon, I realised how we might make the Stone of Peace the cornerstone for our own peace mission. The meeting with Arik was utterly unexpected -I was staying in New York with a Swiss friend at his Manhattan apartment, and the place was suddenly crawling with security ... the kind of security that only Middle Eastern leaders can generate. My friend joked with a bodyguard, “Who do we have upstairs? Arafat and Sharon?” “Just Sharon,” came the answer.

Too good a chance to miss. Too good a synchronicity. I believe these strange coincidences are planned for us, perhaps millions of years in advance, by an intelligence we cannot begin to comprehend. And I saw Michael’s magic working again. Even the bodyguards moved in stop-start motion. Even the prime minister looked up and reached forward and froze and moved again. I saw the thought written on his face: “Michael Jackson! That’s Michael Jackson!”

I knew then that Michael’s blessing could work on the warring factions of the Holy Land. We are planning a visit, for June or July of this year, to meet the Israeli president and the Kings of Jordan and Morocco. I have hopes that Arafat too and the leaders of Hizbollah might be willing to sit down with us. We won’t expect anyone to negotiate -we are not negotiators or politicians, nor miracle workers. All we can do is hope that music and rhythm and the power of pop can indeed work a miracle where politics and religious schism fail tragically every day. It is not only we who need this mirage of peace to become real, after all - it is our children, and their unborn children, and all the songs that they will sing."

Michael Jackson (2002)

"The crush inside the vast record store on Oxford Street was getting scary. I wanted to back out, but the bodyguards behind me had linked elbows. We had to push forwards, through the press of screaming, chanting faces: "My-curl, My-curl, My-curl!" People were laughing and crying at the same time. A young man was jostled to the front of the crowd, a mobile phone pressed to his ear. He was yelling, "You won't believe this, Mum! Michael Jackson is right in front of me, I wish you could see him!" And Michael reached out gently, took the phone and whispered, "Hi, who is this? Yes, really, this is me." The chanting hushed as the whole store strained to hear Michael's murmured conversation. I heard him say, "I love you more," and then he handed back the phone, and the screaming started again.

Outside, a surge of fans almost knocked an elderly woman off her feet as Michael emerged. There were at least 2000 people, and for the woman - who was, I discovered later, simply a passer-by - this must have been terrifying. What happened next, you may not believe. I have proof, because my brother-in-law, Shipi, was filming the scene from the 'chase' car, the bodyguard vehicle parked behind Michael's limo. Michael Jackson is a big man - in my imagination, before I met him, he was a man-child, but in reality he is nearly six feet tall with hands like a baseball catcher. He reached out an arm to steady the woman, and then half led, half carried her to the cars. The throng was too tight around the limo, so Michael ushered her into the chase car, and Shipi kept filming as Michael, very shyly, very formally, introduced himself. The woman, who might have been 80, acted with the poise characteristic of her generation, and politely demanded to be taken to her friend's house in Wimpole Street. So the biggest-selling black artist in history turned bus boy and, as they inched through the traffic, Michael told her all about his beloved children, and how badly he missed them.

The besotted frenzy of the crowd took a much darker turn hours later on Paddington's Platform Eight. Our limo pulled up beside our carriage on the Royal Train, which we had hired to take us to a charity spectacular at my football club, Exeter City. As we climbed out, Michael was separated from his minders. A knot of people lunged forward, and I saw him stumble. For a sickening moment he was out of sight amid the threshing bodies. I realised, with a lurch of horror, that he could have been kicked down onto the tracks, into the wheels. I was sweating with anxiety when he emerged, ten seconds later, scrambling under the arms of the fans with their posters and placards. We sprinted for the carriage door and I helped him through. He tumbled into a seat, his hair plastered to his face. I felt so badly for him that I couldn't even trust myself to ask if he was all right. He always calls me by my full name - not "Uri", not "Yuri" as the Americans say it, not "Geller" (as Shipi does when he is cross with me!). Michael invariably addresses me as "Uri Geller." And I had a sick certainty he was going to tell me, "Uri Geller, I could have been killed, and it was your dumb, stupid fault." But what he actually said, with a beatific grin that made me burst out laughing with relief, was: "I'm OK, Uri Geller. Don't worry. Don't be angry with the people out there, because they didn't know what they were doing. And I love them." I'm Jewish, but at that moment I thought of another man who said, "Forgive them, for they know not what they do." And if that sounds ludicrous, it's because you don't know Michael. It's not as though I've known him for ever.

Back when the Jackson Five were ruling the charts, and when Michael was storming to the King of Pop's throne, I would have loved to have met him. He just never went to parties. And when enemies turned on him in the Nineties, I could smell the stench of an establishment fit-up, because I'd taken a serious kicking from people who used the same foul weapons - slander campaigns, innuendo, trial by media. I thank God the mudslingers haven't aimed the kind of dirt and filth at me that Michael has suffered. We were introduced by Mohammed Al Fayed, who is happy to be the man who owns Michael's favourite shop. People ask where Mo gets the millions to finance Fulham FC - they haven't seen Michael go shopping. He cuts a swathe through department stores like a bulldozer in a china shop. And I mean bulldozer: whole counters are wiped clean. I was with him in the toy department when a bodyguard mentioned his two step-children - that guy is a world champion kick-boxer, with the muscles to match the belts, but it took him three trips to get all his packages down to the cars. Somewhere in Devon, two kids own every fragment of Star Wars merchandise on the market. Michael adores Star Wars. For our first meeting, I flew to New York, where he was recording Invincible, his $30 million album which was finally released last year. We were quickly friends, and he asked me to design part of the CD artwork. Later, we took his children to a private screening of Star Wars episode one, the Phantom Menace. Michael was agog in the seat next to me, whispering his favourite lines - but at one instant, when I turned to point out some detail, he was gone. I sat back, sadly. I thought I knew what this was: the silent goodbye of a man too shy for farewells. My new friend didn't want to send me off with false smiles and empty promises. We probably wouldn't meet again. But then I caught a movement at the edge of my vision and turned to see Michael at the back of the cinema, blissed out in his doll-like dancing, grooving on the soundtrack of Star Wars. He slips into fragments of song all the time - in the lift, in hotel corridors, in the car. Just as it is a revelation to watch him dancing for fun, it is insanely wonderful to hear that voice swinging a few bars of some soul standard.

Maybe if I'd ever seen Fred Astaire hot-step across a hotel lobby, if I'd ever overheard Sinatra shoo-bee-doo-bee-bopping to a blonde in a dark corner of a Vegas bar, I might have felt the same thrill. Maybe. Now there is open warfare with his record company, Sony. Industry insiders believe the real issue is not Michael's career but his ownership of the richest back catalogue in the business - the Lennon-McCartney songs. Michael believes the suits are enraged beyond all reason that a black man holds the gaudiest prize in their world. He also believes the Beatles rights are a bagatelle beside his own crown jewels - his children. When he flew to England in June for his Exeter speech, he desperately wanted to bring his children. And knew he couldn't. The paparazzi would have ripped him apart to get pictures of those beautiful kids. I believe Michael envies what John Lennon did when Sean was born, stepping back from his career and spending four or five years as a full-time parent. The brutal ambitions of his father for the Jackson children is well known. I have never asked Michael about his childhood, because when I am with friends I am interested only in the present moment. But my mother's ancestor, Sigmund Freud, would not have found it difficult to see the connection between a childhood all at sea on heaving emotions, and a father who insists on being a rock for his own children. For such a gently spoken man, Michael is hard as granite when protecting his son and his daughter. That love finds an echo in his affection for his fans. They shout out, "Michael, we love you," and he always answers, "I love you more." I have seen him shrug off his bodyguards to step into a crowd who had waited through a downpour to see him - he signed every poster, every album, and stood there for 20 minutes, listening to the fans' stories, until he was shivering. His foot was in bandages that day, because of a broken bone.

Later, I saw the dressing was sodden. It must have been agony, but his face never showed it. Oh yeah, his face - that's what everyone asks about. And this always shuts them up: "Ask me anything," I say, "but ask yourself first why you feel free to comment on his colour and his looks, when you profess that you never judge anyone by their skin or their face." He changes his hotel room every few days, and I have to remember next time I call to ask for Mr Robinson instead of Mr Brown or Mr Williams. With each switch, he checks all the drawers and cupboards himself. "Lost your passport?" I joked once. "I don't want to leave any gifts behind," he told me earnestly. He keeps everything his fans give him. I couldn't credit this at first, but he truly keeps everything, and always has. If you ever gave Michael a drawing, or a letter, or a soft toy, a jewellery case overflowing with diadems or a plastic hat from McDonalds, he has kept it. "I have packets of M&Ms from 30 years ago," he promised me. "Some day, I'll build a museum for it all."

This week, I have been talking with senior engineers from a space agency, about an eight-year plan to finance a base on the moon by enrolling some of America's super-rich into a private space race. The idea was Michael's: "I want to moonwalk," he said one day, and I told him not to be embarrassed about dancing when I was around. "No, see, really. I want to walk on the moon." There is no doubt that this extraordinary man will get exactly what he wants. The man in the moon better expect a visit. And the suits in the music industry can expect more rockets too."